Existential OCD

Photo by: Turning Point Psychological Services

“I don’t know if I should continue therapy,” announced Linda after spending a couple of minutes in a reflective silence at the beginning of the session. “What’s the point of all this? We all are going to die anyway. No amount of therapy will give any meaning to my life. It’s all useless.”

Ian, a gifted, over-achieving teenage boy has lately fallen behind at school. He finds it impossible to concentrate on anything except finding the answer to the question that haunts him day and night: “How can I know for sure that I really exist? What if somebody is just manipulating my brain and creates the illusion of my experience?” Ian feels that until he can be certain that his experience of life is real and is not created artificially, he can’t continue his regular daily life. He sometimes pinches himself trying to discern his perception from reality, but then he realizes that his perception of the pain may also be artificially created. He also stares at the mirror trying to figure out if the reflection is really his. But again, he feels there’s no way to know for sure. He keeps asking his parents if he is real and if they are real, but he is never satisfied with their answers. “Their claims that all of us are real can also be pre-programmed or manipulated,” he says.

Zoran, a 23-year-old university student has always been preoccupied with philosophical matters. His parents encouraged it and as a family, they engage in intellectually stimulating discussions about the nature and meaning of life. Gradually, though, his parents started to notice that Zoran’s goal in those discussions was to reach a conclusive answer to his unanswerable questions. They also started to notice that these discussions often caused Zoran increasing distress when they discussed the uncertainty of the topics. The parents then tried to stop these philosophical debates, but Zoran became very angry. He followed his parents around the house and demanded that they answer his philosophical questions and listen to his monologues of philosophical quandaries.

Down the Philosophical Rabbit Hole

Many of us have questions that can’t be answered. Philosophers, writers, and poets devoted their lives to pondering such questions. But sometimes, these philosophical quandaries feel endless, pervasive, and torturous, and often interfere with a person’s ability to enjoy life. This is a cue that the person consumed by them may suffer from existential OCD.

Existential OCD is characterized by searching for answers to unanswerable, abstract queries. If you have this kind of OCD, you may be preoccupied with the philosophical aspects of life. You may feel that it’s impossible to continue living until you find an answer to your unresolvable questions. The constant fixation on philosophical or mystical issues most likely leads to incredible distress and interferes with daily functioning.

This OCD type is often mistaken for genuine interest in philosophy. Teachers, university professors, family members, friends, and therapists frequently inadvertently contribute to the worsening of this type of OCD. They indulge the OCD sufferer by engaging in deep intellectual discussions. But for the person with OCD, this endless quest for answers is a source of unbearable pain, frustration, fear, exhaustion, and, often even depression. Even if these discussions achieve some temporary alleviation of pain, in the long run, they just lead to an increase in obsessions and doubts.

Obsessions typical for existential OCD:

- What is the meaning of life?

- What if there is no meaning to life?

- What is my purpose?

- What is life’s purpose?

- Am I real?

- Are you real?

- Is our life real?

- How do I know that the world around me is real?

- Is this conversation that we are having real?

- How do I know that me, is really me?

- How do I know that this is not a simulation of reality?

- Why are we here?

- What if I don’t really exist?

- What is my true calling?

- What if all of this is happening in my dream?

- Are we really here in the room right now?

- We will all die, so what is the point of anything?

- Is the person I see in the mirror really me?

- What if all of this is staged?

- What is reality?

- What if we are just pawns in somebody’s game?

- What if my life is actually somebody’s video game?

- What if I am in a coma?

- Are my sensory perceptions the same as the other people’s?

- What if my brain is held in a jar and is manipulated by somebody?

- What if I’m the only conscious person on the planet and everything else is a pre-programmed character/ an npc?

- What if all the people that I care about and love are not real?

- What does it mean to be my true, authentic self?

- What is my true identity?

- Compared to the vast universe, we are all just meaningless specks. What if there is no point to our lives?

Typical Compulsions for Existential OCD:

As with all the other OCD types, the compulsions are directed at reducing the distress caused by the obsessions and attemps to achieve certainty. They are aimed at resolving the problem, finding out the answer, figuring it all out, or at least, avoiding the triggers or neutralizing the anguish.

- Researching and reading philosophical, psychological, or theological books, blogs, and online forums trying to find the answers to the unanswerable questions.

- Constantly questioning reality.

- Mentally reviewing your days trying to see if they felt real.

- Engaging others in conversations about the meaning of life or about what is real and what is not. This is usually done under the pretense of just being curious about the subject.

- Trying to mentally figure out the answers to your existential questions.

- Avoiding triggering movies, such as The Truman Show, The Matrix, or Inception, or TV shows addressing philosophical topics.

- Ruminating on existential topics.

- Taking philosophy courses with the goal of finding answers to your questions.

- Trying to distract yourself.

- Trying to find physical evidence that the world around you is real and/or that it’s not staged.

- Trying to find physical evidence that you exist (looking in the mirror, pinching yourself, monitoring your physical sensations).

- Constantly looking for reassurance (asking friends, family members, clergy members, researching, watching YouTube, etc.).

- Asking family members if you are real.

- Asking family members if they are real or if the other family members are real.

- Disconnecting from the moment and interpreting it as an alternative “experience.”

- Checking to see if you’re “in control” or if someone is controlling you.

- Comparing how you feel now to how you felt in previous moments or to other similar situations to see whether it’s a real feeling or not.

- Looking for déjà vu experiences and interpreting them as the evidence of reliving the past, which means that the present may not be real.

- Thinking about causing pain to a family member to see if they feel the pain to ensure they are real.

- Mentally reviewing the evidence trying to find an answer to the obsessive question.

The Difference Between Existential OCD and Regular, Non-OCD-Related Philosophical Interests

Like with other OCD types, people with existential OCD often question whether they have OCD or if they are just inquisitive about issues related to the meaning of life. The hidden function of this questioning is usually to find a justification to continue doing compulsions, as stopping them (that is, accepting that there is no definitive answer to the existential questions) seems too scary. In fact, this questioning is, by itself, another obsession (“What if it isn’t OCD and by stopping my research, I will be left with unanswered questions forever and will never be able to live a normal life?” – or some other variation of this question.)

This type of questioning is not any different from trying to justify other types of OCD. For example, people with religious scrupulosity OCD may insist that they are just spiritual people, or people with relationship OCD (ROCD) may claim that they simply value relationships, people with real event OCD may maintain that they just want to find closure, and people with illness anxiety may insist that they just want to be prudent in taking care of their health.

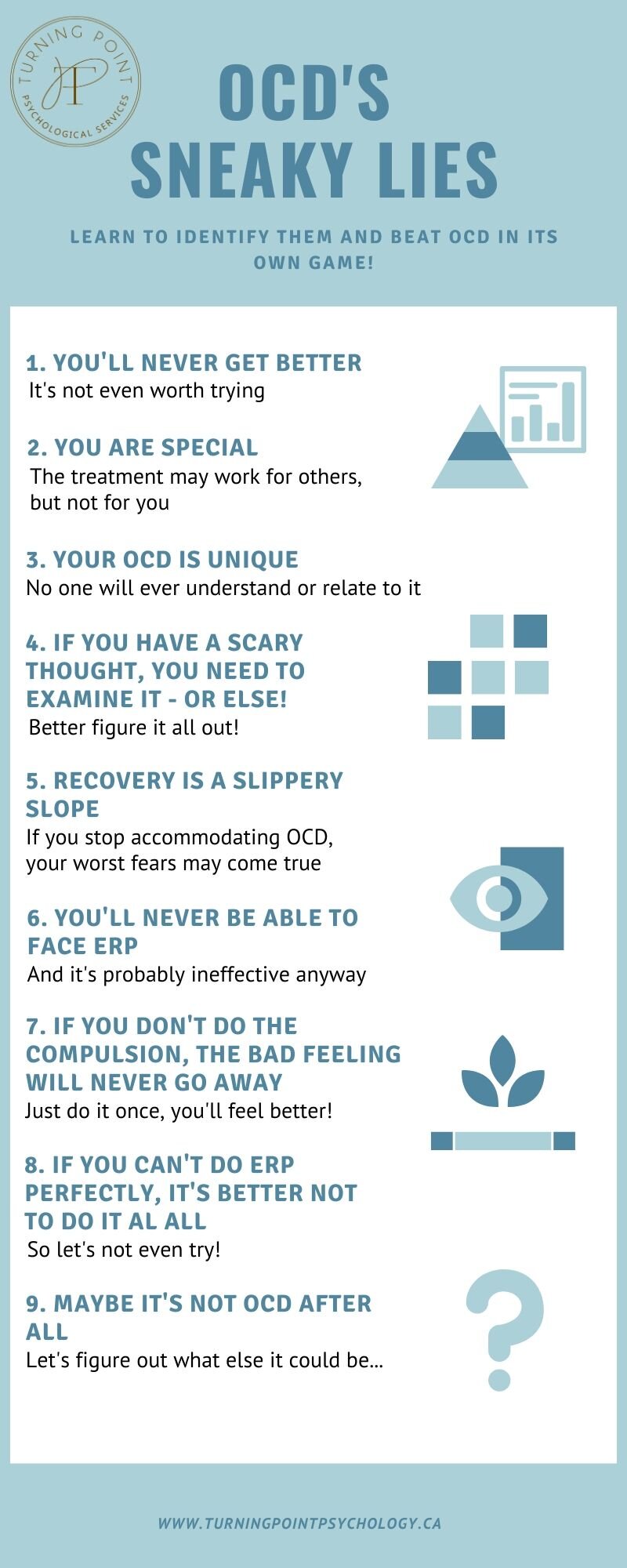

Point is, pretending not to be OCD is one of OCD’s most insidious lies.

So, what is the difference between an OCD sufferer and a philosopher?

As with all other OCD types, it’s not the content of the thoughts that determines whether it’s OCD, but the process of how you relate to the thought.

People who are interested in philosophical subjects and who don’t have OCD usually enjoy learning about this subject. They live their regular day-to day life without being tormented by intrusive thoughts. They don’t have an overwhelming sense of urgency to figure things out and they don’t feel incapable to live with uncertainty.

OCD sufferers, however, often find the research and examination painful and feel unable to stop. For them, research is not driven by curiosity, but rather by the burning need to alleviate their discomfort caused by their existential obsessions.

Here are some signs that your philosophical dilemmas are likely driven by OCD:

- Your thoughts cause you a lot of distress.

- Sometimes you feel proud for being such a deep person who is concerned with profound matters of life, death, and meaning. But most of the time, these thoughts lead to a great deal of suffering and the questions and the attempts to answer them seem endless.

- Your “why” questions always lead to more “why” questions in an infinite, unresolvable stream of thinking.

- You are desperately trying to get rid of your thoughts by seeking reassurance, distracting yourself, avoiding triggering topics, neutralising the thoughts, and trying to think positively.

- You feel that you just have to find the definite answer to your un-answerable thoughts (as opposed to simply being curious and exploring the subject without the need to find an answer).

- You spend a lot of your time ruminating about these unresolvable matters.

- You get lost in these thoughts and feel unable to unhook and get back to the present moment.

- Your attempts to find answers are time-consuming and interfere with living your life.

- You experience a sense of urgency to find answers and certainty once and for all.

- You feel that you are unable to enjoy life until you figure things out.

- No amount of information is enough.

- No amount of reassurance is enough.

- You find yourself going deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole of the Internet trying to find relief.

- You just have to know for sure!

If you’re still unsure whether it’s OCD, it is always a healthier approach in any case of doubt to err on the side of caution and deem your thoughts as OCD and treat them as such.

Treatment of Existential OCD

As with all OCD types, it’s not the obsessions that keep OCD going, but the compulsions.

Obsessions are usually accompanied by a very strong feeling of fear, anxiety, or distress. Compulsions are an attempt to decrease that feeling. The more you resort to compulsions, the more you are teaching your brain to generate additional, sticky intrusive thoughts. By compulsing, you are sending the message to your brain that the questions it produces are important and urgent. You are also learning that compulsions are the only way to obtain relief and thus, you resort to performing more and more of them.

Since compulsions make OCD stronger, the goal of OCD treatment is to teach you that you can experience obsessions and do nothing about them. In other words, to stop the compulsions. You can learn to have these thoughts, let them come and go, and continue living your life in the present without dropping everything in order to figure your obsessive thought out.

The best treatment for OCD is a combination of Exposure with Response Prevention (ERP) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

The treatment will help create new pathways in your brain where you don’t compulse, in spite of having the obsessive thought.

Some Exposure Exercises for Existential OCD:

- Watching triggering content on TV or YouTube (if you have been avoiding it). Movies such as The Matrix, Inception, and The Truman Show are great existential OCD exposures.

- Staying away from any philosophical literature if you’ve been compulsively reading it (OR reading philosophical texts if you’ve been avoiding them).

- Saving or screenshotting news headlines about mystical occurrences, life after death, living in a computer simulation, or UFOs and looking at the screenshots on your phone throughout your day.

- Reading news articles or watching clips about unexplained occurrences and phenomena.

- Creating a screensaver on your computer or your phone that says, “You may never ever find out…”

- Writing on your mirror: I may never know for sure…

- Creating scrips about potentially never finding out what the meaning of life is.

- Creating scripts about perhaps never knowing for sure whether you are real or not.

The scripts may address a scenario of spending your whole life not knowing. Or looking back at your life on your deathbed and still not knowing. Or never really figuring out the true meaning of life. Or finally realising that life has NO meaning. Basically, the script can involve any content about learning to live with uncertainty. Again, the goal of the scripts is to learn to face your fears without resorting to compulsions.

As stated above, the most important part of doing the exposures is to combine them with response prevention (that is, facing the scary scenarios without doing anything to try and alleviate the uncertainty or discomfort).

A Warning About Ineffective and Potentially Harmful Treatment

Beware of a therapist that will give the content of your OCD thoughts too much attention.

A therapist who does not have in-depth knowledge of cognitive and behavioral processes that underlie OCD may engage with you in discussions about your existential questions. Such a therapist may also try to reassure you. Or, he or she may attempt “cognitive restructuring” by exploring your thoughts, examining the evidence that supports or disproves them, seeing how they may relate to your core beliefs, or coming up with some more “realistic” or “positive” thoughts.

All this may make you feel better for a short time, but these discussions are nothing but compulsions. You will likely find yourself questioning the discussion that happened in the session and coming up with more questions and concerns. So, choose your therapist wisely.

16 Steps You Can Start Taking Today If You Have Existential OCD:

These steps will help you gradually reclaim your life by learning that you do not have to waste your time compulsing. You can live with your questions, with your uncertainty, and without knowing. Instead of compulsing, you can concentrate on being the person you want to be even if you never figure out the answer to your OCD’s questions.

1. Take an inventory of what you have lost to OCD so far. How has being in your philosophical head affected your relationships? Your work or studies? Your health? Your joy?

Write these things down and use them to motivate you on your journey to recovery.

2. Reflect on your past attempts to figure things out. Have you found a strategy that has led to the permanent disappearance of your obsessions? If you haven’t – time to give up trying and stop wasting your time.

Acknowledge that you have spent more than enough time trying to find THE ANSWER. Make a choice to try a different strategy.

3. You have done a lot of things to find the answer to your questions and know for sure. How about concentrating on living with not knowing? It is difficult, yes. And yet it is the only way to live this uncertain life. You are living with uncertainty in every other area of your life. We can only really be in the present moment (and not in our head) if we give up the hope to find certainty.

4. Remember that even though the content of your obsessions may seem different, unique, or special - in reality these are just thoughts and they are not unlike any other thoughts that your brain generates. It’s giving these thoughts special attention and treating them as important and urgent that drives your OCD.

5. Develop a habit of noticing your thoughts and the way they hook you. Take a step back and say to yourself, “Hey, here’s another one of these thoughts.” “Here’s the familiar sense of urgency.” ”I notice an urge to check/figure out.” “Here’s my meaningless life story.” Do nothing about these thoughts. Observe them with curiosity without engaging with them.

6. Practice sitting with the difficult feelings that are connected to your obsessions and do nothing to get rid of these feelings. Practice letting these feelings come and go at their own time without trying to MAKE them go. Do it regardless of how distressful and difficult the feelings are. Just let them be.

7. Stop reading and researching anything related to existential topics.

8. Tell your family members and friends that you are working on getting your life back and explain that they need to stop engaging in philosophical discussions with you, even if you beg them to do so. Create a code word or a code sentence that they can reply with when you ask them philosophical questions. For example, they may say, “I love you and that’s why I don’t want to engage with your OCD.” Or, “it seems your OCD is tricking us into entering the rabbit hole again.” Encourage them to respond (lovingly and patiently) with these words/sentences instead of being sucked into another discussion.

9. Make a similar agreement about reassurance. Ask your family members to respond supportively, but firmly each time you ask for reassurance. They may say, “I don’t know the answer to this. I get that it’s hard, but we can live with not knowing.”

10. Limit yourself to a certain number of reassurance-related questions per day or per week and work on gradually diminishing this number. Use these reassurance coupons and do not exceed the agreed-upon number of coupons for the week.

11. Watch distress-inducing movies that you have been avoiding. Do nothing to try and reduce the distress.

12. Take some index cards. Write your existential questions on one side of the cards. On the other side, write: “I may never know.” Carry these cards with you. You can also give these cards to your family members if you tend to ask them these questions. When you ask the question (again) the family members can show you the question written on the card, and then the back side of the card with “the answer.”

13. Stop ruminating. That is, stop trying to find the answers in your head by mentally reviewing the information, trying to figure things out, checking, and otherwise attempting to find a solution to your obsessions. Remember, rumination is not the same as having your initial obsessive thought. You don’t have control over the thoughts that pop into your head (obsessions). But you do have control over whether you are choosing to engage with them (rumination).

14. Learn to live with not-knowing. You may never know. Make a script about not knowing.

15. Engage in Life! Bring your full attention to the things that matter to you and make a choice of taking steps toward the life you want to live and the person you want to be. You don’t have an answer right now. Maybe you’ll somehow find the answer in the future. Or maybe you never will. Regardless, you can choose to be the best version of yourself at this very moment.

16. If you can, find an OCD specialist who can help you build the foundation for OCD treatment via ACT strategies, structure your ERP, and guide you toward recovery.

Think you or someone you know may have existential OCD? Share your story in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this article, follow us on Facebook for more great tips and resources!

Anna Prudovski is a Psychologist and the Clinical Director of Turning Point Psychological Services. She has a special interest in treating anxiety disorders and OCD, as well as working with parents.

Anna lives with her husband and children in Vaughan, Ontario. When she is not treating patients, supervising clinicians, teaching CBT, and attending professional workshops, Anna enjoys practicing yoga, going on hikes with her family, traveling, studying Ayurveda, and spending time with friends. Her favorite pastime is reading.

Related Posts

-

Anxiety

- Jul 5, 2020 Anxiety and Related Disorders

- Jun 2, 2020 Panic Disorder

- Jul 7, 2019 Social Anxiety Disorder: Facts, Symptoms, Treatment, and Tips for Managing It.

- Jun 6, 2019 10 Popular Therapy Strategies that Don’t Work for Bad Anxiety or OCD

- Mar 6, 2019 10 Tips for Dealing with Anxiety

- Feb 7, 2019 Don’t Feed the Dinosaurs or How to Face Your Anxiety

- Jan 22, 2019 Meet Anxiety. Anxiety: Part 1/7

- Dec 24, 2018 Why does Anxiety Interfere with My Life So Much? Anxiety: Part 2/7

- Dec 17, 2017 Anatomy and Physiology of Anxiety. Anxiety: Part 3/7

- Dec 3, 2017 Dealing with Anxiety Components One by One. Anxiety: Part 4/7

- Nov 12, 2017 The Discovery of Oz the Terrible. Anxiety: Part 5/7

- Oct 8, 2017 Meet Your New Best Friend: Uncertainty. Anxiety: Part 6/7

- Sep 10, 2017 Some More Strategies to Help You Deal With Anxiety and Worry. Anxiety: Part 7/7

-

OCD & Co.

- Nov 23, 2021 Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for OCD

- Sep 13, 2021 Relationship OCD (ROCD) and Its Treatment

- Jul 12, 2021 Existential OCD

- Jun 8, 2021 Real Event OCD and 10 Steps to Getting Better

- Apr 17, 2021 Signs That You or Someone You Know May Have OCD and Not Realize It

- Dec 2, 2020 Don’t Argue With a Brain Glitch. (10 Do's and 5 Don'ts for Parents of Kids with OCD)

- Sep 25, 2020 Do I have OCD? 8 Surprising OCD Myths

- Aug 15, 2020 9 Surprising Things We Don’t Do When Treating OCD at Our Clinic

- May 21, 2020 Illness Anxiety and How to Overcome It

- Feb 21, 2020 OCD and Online Romance Scam

- Jun 6, 2019 10 Popular Therapy Strategies that Don’t Work for Bad Anxiety or OCD

- Nov 17, 2018 Is it Possible to Be “a Little OCD?”

- Oct 23, 2018 Defeating the (Seemingly) Indestructible OCD Hydra: 8 Effective Tricks to Deal with New Obsessions.

- Oct 22, 2018 OCD, is That You Again? How to Know if Your New Thought is OCD, and 6 Concrete OCD-Repelling Strategies for You to Start Practicing Right Away.

- Oct 21, 2018 Trich or treat? Are you secretly pulling your hair out? Trichotillomania and its Treatment

- Apr 26, 2017 Stepping Off the OCD Hamster Wheel. A Therapist's Recovery Journey

- Parenting

-

Psychology

- Aug 21, 2019 The Road to ‘Stuckness’ is Paved with Good Intentions

- Sep 4, 2018 Having Difficulty Making Decisions? This Subtle Shift in Your Perspective May Change the Way You Approach Decisions from Now On.

- Aug 17, 2018 A Gentleman in Moscow or How to Live Life

- Jul 1, 2018 Who Goes to Therapy? Myths Versus Reality: The Therapist’s Perspective

- May 1, 2018 Do you often ask this innocent question? Watch out – you may be at risk for depression, anxiety, and other disorders.

- Feb 3, 2018 An effective hack to instantly take the edge off a negative emotion